|

|

Cultural Context: Nurses' Work and Organization Culture

Despite the myriad of cultural lens evident across disciplines, including nursing, one unifying concept appears constant across the theories: the concept of context. Nursing culture is situated within the bureaucratic context of the health care system, manifested across various institutional settings, including hospitals, community health agencies, and other specialized offices and clinics. These settings are operationalized by the organizational cultures formed to govern and implement health care. “The health system has become a production process with structured input – output flows (selection, prioritization, performance/quality control, discharge/disposal, serving consumption (consumers of the product/commodity). It has a command structure (hierarchy) and a complex division of labor. It has an ideology: mental patterns codified in policies and procedures, rules and regulations” (Hunt, 2004, p. 200). Health organizational culture is based on a bureaucratic, service-quality model that “shapes the environmental stimuli and experiences to which one is exposed and to which one will react” (Gifford, 2002, p. 14). Despite the myriad of cultural lens evident across disciplines, including nursing, one unifying concept appears constant across the theories: the concept of context. Nursing culture is situated within the bureaucratic context of the health care system, manifested across various institutional settings, including hospitals, community health agencies, and other specialized offices and clinics. These settings are operationalized by the organizational cultures formed to govern and implement health care. “The health system has become a production process with structured input – output flows (selection, prioritization, performance/quality control, discharge/disposal, serving consumption (consumers of the product/commodity). It has a command structure (hierarchy) and a complex division of labor. It has an ideology: mental patterns codified in policies and procedures, rules and regulations” (Hunt, 2004, p. 200). Health organizational culture is based on a bureaucratic, service-quality model that “shapes the environmental stimuli and experiences to which one is exposed and to which one will react” (Gifford, 2002, p. 14).

Modernist Excellence Contexts

Since the early 1980s, major health care institutions have tended to move toward a modernist excellence tradition that focuses on a culture of service quality. “Excellent organizations are the way they are because they are organized to obtain extraordinary effort from ordinary human beings. Promoting culture as a social glue and source of increased productivity, they engaged with the reproduction of the strong cultural claims” (Beil-Hildebrand, 2002, p. 259). Organizational culture is most clearly witnessed and experienced by nurses through the influence of structure, function, process, time and space/place. Since the early 1980s, major health care institutions have tended to move toward a modernist excellence tradition that focuses on a culture of service quality. “Excellent organizations are the way they are because they are organized to obtain extraordinary effort from ordinary human beings. Promoting culture as a social glue and source of increased productivity, they engaged with the reproduction of the strong cultural claims” (Beil-Hildebrand, 2002, p. 259). Organizational culture is most clearly witnessed and experienced by nurses through the influence of structure, function, process, time and space/place.

The structure of health care is reminiscent of the centralized bureaucratic control described by Weber (1946). Cost control, resource restraints, and modernist structure create enormous pressure for nurses within the workplace culture. “Management has the power to control the supply of the other things necessary for the provision of health care, e.g. Type of cases, number of clients per nurse, and the supply of health care professionals” (Beil-Hildebrand, 2002, p. 267).

The Discourse of Best Practice

Organizational culture is ultimately co-constructed by the various participatory groups within the functional and structural confines established by the upper bureaucratic power holders (Wong & Tierney, 2001). One process that is commonly applied within health care that perpetuates the dominance of modernist discourse is the application of 'best practices'. Best practices relates to the use of benchmarked standards for health care service quality that shapes and often confines nursing care to adhere to the manipulation and constriction of time, resource use, and energy expenditure when providing nursing care within the organizational culture. “Uncritically adopting best practices is inadequate unless it addresses the power relationships that shape the consciousness of the players. Failure to expose the power relationships between employers, employees, consumers and the organization to whom best practice is benchmarked ignores the social context in which particular best practices are located. Further, it reflects the power of dominant groups to shape its direction” (Smith & Sulton, 1999, p. 103). Organizational culture is ultimately co-constructed by the various participatory groups within the functional and structural confines established by the upper bureaucratic power holders (Wong & Tierney, 2001). One process that is commonly applied within health care that perpetuates the dominance of modernist discourse is the application of 'best practices'. Best practices relates to the use of benchmarked standards for health care service quality that shapes and often confines nursing care to adhere to the manipulation and constriction of time, resource use, and energy expenditure when providing nursing care within the organizational culture. “Uncritically adopting best practices is inadequate unless it addresses the power relationships that shape the consciousness of the players. Failure to expose the power relationships between employers, employees, consumers and the organization to whom best practice is benchmarked ignores the social context in which particular best practices are located. Further, it reflects the power of dominant groups to shape its direction” (Smith & Sulton, 1999, p. 103).

Nurses are the largest group of health care professionals, and they work, perhaps unknowingly, to support the modernist discourse of health care. Although medicine is considered a more powerful discipline, the work and status of physicians is less controlled, and more flexible within the context of health care service (Beil-Hildebrand, 2002). Nursing culture is shaped by management initiatives such as best practices which creates a stasis, a performance marker which may support the achievement of standards, but restricts the activity and autonomy of nurses in general. “Maybe language that incorporates the use of the term 'better practice' is more indicative of reality as it indicates a practice that is progressive and dynamic. It indicates a practice that is continually evolving and improving rather than having reached a pinnacle of performance” (Smith & Sulton, 1999, p. 103). Nurses are the largest group of health care professionals, and they work, perhaps unknowingly, to support the modernist discourse of health care. Although medicine is considered a more powerful discipline, the work and status of physicians is less controlled, and more flexible within the context of health care service (Beil-Hildebrand, 2002). Nursing culture is shaped by management initiatives such as best practices which creates a stasis, a performance marker which may support the achievement of standards, but restricts the activity and autonomy of nurses in general. “Maybe language that incorporates the use of the term 'better practice' is more indicative of reality as it indicates a practice that is progressive and dynamic. It indicates a practice that is continually evolving and improving rather than having reached a pinnacle of performance” (Smith & Sulton, 1999, p. 103).

Time and Space in Context

Time is another concept that is used to control nursing practice within organizational culture. “Monochronic cultures are oriented towards tasks, schedules, and procedures and measured by the external standard of the clock which conceptualizes time as existing outside the individual with dehumanizing effects as the external order of the clock is enforced at the cost of blindness to the humanity of its members” (Jones, 2001, p. 153). Andrew Abbott (1997) described the notion of locatedness, credited to the Chicago School mode of thought, as the context for “social facts and the importance of contextual contingencies” (p. 1158). “...one can not understand social life without understanding the arrangements of particular social actors in particular social times and places. No social fact makes any sense abstracted from its context in social (and often geographic) space and social time. Social facts are located” (p. 1152). Time is another concept that is used to control nursing practice within organizational culture. “Monochronic cultures are oriented towards tasks, schedules, and procedures and measured by the external standard of the clock which conceptualizes time as existing outside the individual with dehumanizing effects as the external order of the clock is enforced at the cost of blindness to the humanity of its members” (Jones, 2001, p. 153). Andrew Abbott (1997) described the notion of locatedness, credited to the Chicago School mode of thought, as the context for “social facts and the importance of contextual contingencies” (p. 1158). “...one can not understand social life without understanding the arrangements of particular social actors in particular social times and places. No social fact makes any sense abstracted from its context in social (and often geographic) space and social time. Social facts are located” (p. 1152).

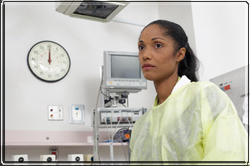

Space/place plays a critical role in how nursing culture is expressed in context. “Hospitals are comprised of multiple and distinctive spaces within which nursing is practiced and nursing identities are constructed and performed” (Halford & Leonard, 2003, p. 201). Nursing culture operates within constrictive spaces (usually hospital units); nurses are also “agents of power in their use of organizational space” (p. 202). As nurses and other health care providers colonize the organizational space to provide health service, organizational space is constructed and becomes a mode of action. Hospital units become the stage where nursing performance occurs and culture is expressed.

Halford and Leonard (2003) observed how nurses used movement within the organizational space to communicate power, authority and to perform nursing practice. “Often, nurses move quickly with purpose but in chore-driven ways: always busy, buzzing around, repetitive spatial patterns, communicating with each other in passing, in snatched conversations” (p. 205). Halford and Leonard (2003) observed how nurses used movement within the organizational space to communicate power, authority and to perform nursing practice. “Often, nurses move quickly with purpose but in chore-driven ways: always busy, buzzing around, repetitive spatial patterns, communicating with each other in passing, in snatched conversations” (p. 205).

As nursing culture moves to more non-traditional community-based settings, a culture of place continues to be an important influence on nursing, as it becomes “more than a physical setting but instead, a set of situated social dynamics” (Poland, Lehoux, Holmes, & Andrews, 2005, p. 171). A culture manifest or distinctive culture of place is created by the routine interactions of the participants and socially controlled organizational processes and structures.

Power in Context

The power relations inherent in organizational culture are situational and relational, occurring within organizational time and space/place. Three dimensions of power can be identified that help to explain situated practice: The power relations inherent in organizational culture are situational and relational, occurring within organizational time and space/place. Three dimensions of power can be identified that help to explain situated practice:

- control of material resources

- control of human resources

- control of ideas (Poland et al, 2005).

These three characteristics mirror three types of cultural forms also identified by Poland et al. (2005), namely:

- material objects or artefacts

- social relations or sociofacts

- ideas or mentifacts

As Foucault pointed out, “power is fluid and circulates among and through bodies. Power acts upon individuals as they, in turn, act upon others” (cited in Holmes & Gastaldo, 2002, p. 559). Despite advances to the contrary, nurses still “experience non-egalitarian, historically situated, non-privileged positions within society, the health care system, and even within nursing” (p. 558). Yet, it is the efficiency and industriousness of nursing culture that makes the perpetual modernist workings of the organizational cultural structure possible. Nurses have less power compared to the administrative hierarchies and the profession of medicine. Yet, within the health care system, nurses express both governmentality and other forms of power, especially pastoral power. Governmentality is exercised as an aim to influence the conduct of individuals, in this case, clients and their families. Foucault defined governmentality as “the ensemble formed by the institutions, procedures, analyses, and reflections, the calculations and tactics, that allow the exercise of this very specific albeit complex form of power which has as its target population as its principle form of knowledge, political economy, and as its essential technical means, apparatuses of security” (1979, p. 20). As Foucault pointed out, “power is fluid and circulates among and through bodies. Power acts upon individuals as they, in turn, act upon others” (cited in Holmes & Gastaldo, 2002, p. 559). Despite advances to the contrary, nurses still “experience non-egalitarian, historically situated, non-privileged positions within society, the health care system, and even within nursing” (p. 558). Yet, it is the efficiency and industriousness of nursing culture that makes the perpetual modernist workings of the organizational cultural structure possible. Nurses have less power compared to the administrative hierarchies and the profession of medicine. Yet, within the health care system, nurses express both governmentality and other forms of power, especially pastoral power. Governmentality is exercised as an aim to influence the conduct of individuals, in this case, clients and their families. Foucault defined governmentality as “the ensemble formed by the institutions, procedures, analyses, and reflections, the calculations and tactics, that allow the exercise of this very specific albeit complex form of power which has as its target population as its principle form of knowledge, political economy, and as its essential technical means, apparatuses of security” (1979, p. 20).

One such security apparatus prevalent in nursing culture is pastoral power, exhibited through care provision using specific standardized therapeutic regimes that promote appropriate normalized activities and ways of living. “The power of normalization imposes homogeneity by setting standards and ideals for human beings. Governmentality connects the question of government and politics to the self” (Holmes & Gastaldo, 2002, p. 560). Nurses are the agents that engage in the regulation, promotion, modification, maintenance, and monitoring of client-environmental interaction and set the stage for therapeutic experiences within the organizational context (Hilton, 1997). Often, the culture witnessed in practice is far different from the espoused culture held dear in the heart of ideal nursing culture (Manley, 2000). Nursing engages in a discourse of holistic care yet operates within a constricted time-space context that reduces care to fragmented regimes (Francis, 1999). “Economical constraints require cheap labor, task-oriented care, and ritualisation of nursing practice provisions” (Mantzoukas, 2002, p. 16) since organizational culture shapes the context and experiences in which nurses act and react (Gifford, 2002). One such security apparatus prevalent in nursing culture is pastoral power, exhibited through care provision using specific standardized therapeutic regimes that promote appropriate normalized activities and ways of living. “The power of normalization imposes homogeneity by setting standards and ideals for human beings. Governmentality connects the question of government and politics to the self” (Holmes & Gastaldo, 2002, p. 560). Nurses are the agents that engage in the regulation, promotion, modification, maintenance, and monitoring of client-environmental interaction and set the stage for therapeutic experiences within the organizational context (Hilton, 1997). Often, the culture witnessed in practice is far different from the espoused culture held dear in the heart of ideal nursing culture (Manley, 2000). Nursing engages in a discourse of holistic care yet operates within a constricted time-space context that reduces care to fragmented regimes (Francis, 1999). “Economical constraints require cheap labor, task-oriented care, and ritualisation of nursing practice provisions” (Mantzoukas, 2002, p. 16) since organizational culture shapes the context and experiences in which nurses act and react (Gifford, 2002).

Nursing Work Culture

The bureaucratic social structure in which nursing culture operates can be an overwhelming context for the new graduate nurse, as well as nurses with seasoned experience (Philpin, 1999). A palpable tension exists between the industrial organizational culture “with its emphasis on the systematic and procedural work culture necessary for mass production” (Hunt, 2004, p. 189) and the ideal nursing culture espoused and initiated during nursing education. As new graduates enter the work culture, they must learn about and adapt to the collective culture through enculturation and acculturation (Hong, 2001). This socialization process acquaints the new nurse to the norms, beliefs, and values of the nursing culture within the specific health care culture of the hospital or community unit. However, neophyte nurses are not “passive sponges who gradually soak up the collective culture in which they are embedded" (p. 12). They can choose to participate, they can also choose to transform it, at least internally, by rejecting aspects that do not feel right, and embracing those that do. “Individual providers construct and reconstruct their own personal version of the collective culture” (p. 12). The bureaucratic social structure in which nursing culture operates can be an overwhelming context for the new graduate nurse, as well as nurses with seasoned experience (Philpin, 1999). A palpable tension exists between the industrial organizational culture “with its emphasis on the systematic and procedural work culture necessary for mass production” (Hunt, 2004, p. 189) and the ideal nursing culture espoused and initiated during nursing education. As new graduates enter the work culture, they must learn about and adapt to the collective culture through enculturation and acculturation (Hong, 2001). This socialization process acquaints the new nurse to the norms, beliefs, and values of the nursing culture within the specific health care culture of the hospital or community unit. However, neophyte nurses are not “passive sponges who gradually soak up the collective culture in which they are embedded" (p. 12). They can choose to participate, they can also choose to transform it, at least internally, by rejecting aspects that do not feel right, and embracing those that do. “Individual providers construct and reconstruct their own personal version of the collective culture” (p. 12).

Cultural Relations and Horizontal Violence

An unfortunate backlash of the tension and pressure of the organizational culture that surrounds nurses is a high incidence of horizontal violence, or staff conflict, especially poor colleague relationships (Farrell, 2001). When this is experienced by new nurses, it can be particularly paralyzing, as “junior nurses are quickly socialized into a culture of nurse-to-nurse abuse. This helps to demonstrate the hierarchical structures and preserve the status quo” (p. 28). An unfortunate backlash of the tension and pressure of the organizational culture that surrounds nurses is a high incidence of horizontal violence, or staff conflict, especially poor colleague relationships (Farrell, 2001). When this is experienced by new nurses, it can be particularly paralyzing, as “junior nurses are quickly socialized into a culture of nurse-to-nurse abuse. This helps to demonstrate the hierarchical structures and preserve the status quo” (p. 28).

Horizontal violence, a notion originally developed to describe the intergroup violence that emerged due to the oppression during Africa's colonization by the British, “embodies an understanding of how oppressed groups direct their frustrations and dissatisfactions towards each other as a response to a system that has excluded them from power” (Freshwater, 2000, p. 482). This behavior is seen as an expression of power, but one that can be quite disempowering, especially for those targeted by the abuse.

If nurses feel alienated, with no control over their own practice, they may experience resentment and frustration which is expressed to those near at hand, usually other nurses and perhaps even their own clients. Nurses are expected to be constantly vigilant, in a “state of watchful attention, of maximal physiological and psychological readiness to act and having the ability to detect and react to danger” (Meyer & Lavin, 2005, p.1). This vigilence coupled with heavy workloads, extreme time pressures, and limited space in which to work creates a very real cultural context of contention. If one nurse sees another nurse as doing less, making mistakes, or invading their space, violent or abusive behaviors can easily occur, perpetuating the cycle of tension and distress. Wesorick (2002) addressed this issue by encouraging health care management and nurses to create healthy, healing work cultures in nursing, “to transform practice cultures so the essence, uniqueness, and outcomes of professional practice will be realized” (p. 18). She points to cultural transformation as the key, which “requires continuous commitment to create a space worthy of the presence, efforts, and needs of those who provide and receive care” (p. 24). This is important not only for a strong healthy nursing culture in context, but for the optimal provision of client-centered, holistic care. If nurses feel alienated, with no control over their own practice, they may experience resentment and frustration which is expressed to those near at hand, usually other nurses and perhaps even their own clients. Nurses are expected to be constantly vigilant, in a “state of watchful attention, of maximal physiological and psychological readiness to act and having the ability to detect and react to danger” (Meyer & Lavin, 2005, p.1). This vigilence coupled with heavy workloads, extreme time pressures, and limited space in which to work creates a very real cultural context of contention. If one nurse sees another nurse as doing less, making mistakes, or invading their space, violent or abusive behaviors can easily occur, perpetuating the cycle of tension and distress. Wesorick (2002) addressed this issue by encouraging health care management and nurses to create healthy, healing work cultures in nursing, “to transform practice cultures so the essence, uniqueness, and outcomes of professional practice will be realized” (p. 18). She points to cultural transformation as the key, which “requires continuous commitment to create a space worthy of the presence, efforts, and needs of those who provide and receive care” (p. 24). This is important not only for a strong healthy nursing culture in context, but for the optimal provision of client-centered, holistic care.

|

|

|

|

|

Despite the myriad of cultural lens evident across disciplines, including nursing, one unifying concept appears constant across the theories: the concept of context. Nursing culture is situated within the bureaucratic context of the health care system, manifested across various institutional settings, including hospitals, community health agencies, and other specialized offices and clinics. These settings are operationalized by the organizational cultures formed to govern and implement health care. “The health system has become a production process with structured input – output flows (selection, prioritization, performance/quality control, discharge/disposal, serving consumption (consumers of the product/commodity). It has a command structure (hierarchy) and a complex division of labor. It has an ideology: mental patterns codified in policies and procedures, rules and regulations” (Hunt, 2004, p. 200). Health organizational culture is based on a bureaucratic, service-quality model that “shapes the environmental stimuli and experiences to which one is exposed and to which one will react” (Gifford, 2002, p. 14).

Despite the myriad of cultural lens evident across disciplines, including nursing, one unifying concept appears constant across the theories: the concept of context. Nursing culture is situated within the bureaucratic context of the health care system, manifested across various institutional settings, including hospitals, community health agencies, and other specialized offices and clinics. These settings are operationalized by the organizational cultures formed to govern and implement health care. “The health system has become a production process with structured input – output flows (selection, prioritization, performance/quality control, discharge/disposal, serving consumption (consumers of the product/commodity). It has a command structure (hierarchy) and a complex division of labor. It has an ideology: mental patterns codified in policies and procedures, rules and regulations” (Hunt, 2004, p. 200). Health organizational culture is based on a bureaucratic, service-quality model that “shapes the environmental stimuli and experiences to which one is exposed and to which one will react” (Gifford, 2002, p. 14).  Since the early 1980s, major health care institutions have tended to move toward a modernist excellence tradition that focuses on a culture of service quality. “Excellent organizations are the way they are because they are organized to obtain extraordinary effort from ordinary human beings. Promoting culture as a social glue and source of increased productivity, they engaged with the reproduction of the strong cultural claims” (Beil-Hildebrand, 2002, p. 259). Organizational culture is most clearly witnessed and experienced by nurses through the influence of structure, function, process, time and space/place.

Since the early 1980s, major health care institutions have tended to move toward a modernist excellence tradition that focuses on a culture of service quality. “Excellent organizations are the way they are because they are organized to obtain extraordinary effort from ordinary human beings. Promoting culture as a social glue and source of increased productivity, they engaged with the reproduction of the strong cultural claims” (Beil-Hildebrand, 2002, p. 259). Organizational culture is most clearly witnessed and experienced by nurses through the influence of structure, function, process, time and space/place.  Organizational culture is ultimately co-constructed by the various participatory groups within the functional and structural confines established by the upper bureaucratic power holders (Wong & Tierney, 2001). One process that is commonly applied within health care that perpetuates the dominance of modernist discourse is the application of 'best practices'. Best practices relates to the use of benchmarked standards for health care service quality that shapes and often confines nursing care to adhere to the manipulation and constriction of time, resource use, and energy expenditure when providing nursing care within the organizational culture. “Uncritically adopting best practices is inadequate unless it addresses the power relationships that shape the consciousness of the players. Failure to expose the power relationships between employers, employees, consumers and the organization to whom best practice is benchmarked ignores the social context in which particular best practices are located. Further, it reflects the power of dominant groups to shape its direction” (Smith & Sulton, 1999, p. 103).

Organizational culture is ultimately co-constructed by the various participatory groups within the functional and structural confines established by the upper bureaucratic power holders (Wong & Tierney, 2001). One process that is commonly applied within health care that perpetuates the dominance of modernist discourse is the application of 'best practices'. Best practices relates to the use of benchmarked standards for health care service quality that shapes and often confines nursing care to adhere to the manipulation and constriction of time, resource use, and energy expenditure when providing nursing care within the organizational culture. “Uncritically adopting best practices is inadequate unless it addresses the power relationships that shape the consciousness of the players. Failure to expose the power relationships between employers, employees, consumers and the organization to whom best practice is benchmarked ignores the social context in which particular best practices are located. Further, it reflects the power of dominant groups to shape its direction” (Smith & Sulton, 1999, p. 103).  Nurses are the largest group of health care professionals, and they work, perhaps unknowingly, to support the modernist discourse of health care. Although medicine is considered a more powerful discipline, the work and status of physicians is less controlled, and more flexible within the context of health care service (Beil-Hildebrand, 2002). Nursing culture is shaped by management initiatives such as best practices which creates a stasis, a performance marker which may support the achievement of standards, but restricts the activity and autonomy of nurses in general. “Maybe language that incorporates the use of the term 'better practice' is more indicative of reality as it indicates a practice that is progressive and dynamic. It indicates a practice that is continually evolving and improving rather than having reached a pinnacle of performance” (Smith & Sulton, 1999, p. 103).

Nurses are the largest group of health care professionals, and they work, perhaps unknowingly, to support the modernist discourse of health care. Although medicine is considered a more powerful discipline, the work and status of physicians is less controlled, and more flexible within the context of health care service (Beil-Hildebrand, 2002). Nursing culture is shaped by management initiatives such as best practices which creates a stasis, a performance marker which may support the achievement of standards, but restricts the activity and autonomy of nurses in general. “Maybe language that incorporates the use of the term 'better practice' is more indicative of reality as it indicates a practice that is progressive and dynamic. It indicates a practice that is continually evolving and improving rather than having reached a pinnacle of performance” (Smith & Sulton, 1999, p. 103). Time is another concept that is used to control nursing practice within organizational culture. “Monochronic cultures are oriented towards tasks, schedules, and procedures and measured by the external standard of the clock which conceptualizes time as existing outside the individual with dehumanizing effects as the external order of the clock is enforced at the cost of blindness to the humanity of its members” (Jones, 2001, p. 153). Andrew Abbott (1997) described the notion of locatedness, credited to the Chicago School mode of thought, as the context for “social facts and the importance of contextual contingencies” (p. 1158). “...one can not understand social life without understanding the arrangements of particular social actors in particular social times and places. No social fact makes any sense abstracted from its context in social (and often geographic) space and social time. Social facts are located” (p. 1152).

Time is another concept that is used to control nursing practice within organizational culture. “Monochronic cultures are oriented towards tasks, schedules, and procedures and measured by the external standard of the clock which conceptualizes time as existing outside the individual with dehumanizing effects as the external order of the clock is enforced at the cost of blindness to the humanity of its members” (Jones, 2001, p. 153). Andrew Abbott (1997) described the notion of locatedness, credited to the Chicago School mode of thought, as the context for “social facts and the importance of contextual contingencies” (p. 1158). “...one can not understand social life without understanding the arrangements of particular social actors in particular social times and places. No social fact makes any sense abstracted from its context in social (and often geographic) space and social time. Social facts are located” (p. 1152).  Halford and Leonard (2003) observed how nurses used movement within the organizational space to communicate power, authority and to perform nursing practice. “Often, nurses move quickly with purpose but in chore-driven ways: always busy, buzzing around, repetitive spatial patterns, communicating with each other in passing, in snatched conversations” (p. 205).

Halford and Leonard (2003) observed how nurses used movement within the organizational space to communicate power, authority and to perform nursing practice. “Often, nurses move quickly with purpose but in chore-driven ways: always busy, buzzing around, repetitive spatial patterns, communicating with each other in passing, in snatched conversations” (p. 205).  The power relations inherent in organizational culture are situational and relational, occurring within organizational time and space/place. Three dimensions of power can be identified that help to explain situated practice:

The power relations inherent in organizational culture are situational and relational, occurring within organizational time and space/place. Three dimensions of power can be identified that help to explain situated practice: As Foucault pointed out, “power is fluid and circulates among and through bodies. Power acts upon individuals as they, in turn, act upon others” (cited in Holmes & Gastaldo, 2002, p. 559). Despite advances to the contrary, nurses still “experience non-egalitarian, historically situated, non-privileged positions within society, the health care system, and even within nursing” (p. 558). Yet, it is the efficiency and industriousness of nursing culture that makes the perpetual modernist workings of the organizational cultural structure possible. Nurses have less power compared to the administrative hierarchies and the profession of medicine. Yet, within the health care system, nurses express both governmentality and other forms of power, especially pastoral power. Governmentality is exercised as an aim to influence the conduct of individuals, in this case, clients and their families. Foucault defined governmentality as “the ensemble formed by the institutions, procedures, analyses, and reflections, the calculations and tactics, that allow the exercise of this very specific albeit complex form of power which has as its target population as its principle form of knowledge, political economy, and as its essential technical means, apparatuses of security” (1979, p. 20).

As Foucault pointed out, “power is fluid and circulates among and through bodies. Power acts upon individuals as they, in turn, act upon others” (cited in Holmes & Gastaldo, 2002, p. 559). Despite advances to the contrary, nurses still “experience non-egalitarian, historically situated, non-privileged positions within society, the health care system, and even within nursing” (p. 558). Yet, it is the efficiency and industriousness of nursing culture that makes the perpetual modernist workings of the organizational cultural structure possible. Nurses have less power compared to the administrative hierarchies and the profession of medicine. Yet, within the health care system, nurses express both governmentality and other forms of power, especially pastoral power. Governmentality is exercised as an aim to influence the conduct of individuals, in this case, clients and their families. Foucault defined governmentality as “the ensemble formed by the institutions, procedures, analyses, and reflections, the calculations and tactics, that allow the exercise of this very specific albeit complex form of power which has as its target population as its principle form of knowledge, political economy, and as its essential technical means, apparatuses of security” (1979, p. 20).  One such security apparatus prevalent in nursing culture is pastoral power, exhibited through care provision using specific standardized therapeutic regimes that promote appropriate normalized activities and ways of living. “The power of normalization imposes homogeneity by setting standards and ideals for human beings. Governmentality connects the question of government and politics to the self” (Holmes & Gastaldo, 2002, p. 560). Nurses are the agents that engage in the regulation, promotion, modification, maintenance, and monitoring of client-environmental interaction and set the stage for therapeutic experiences within the organizational context (Hilton, 1997). Often, the culture witnessed in practice is far different from the espoused culture held dear in the heart of ideal nursing culture (Manley, 2000). Nursing engages in a discourse of holistic care yet operates within a constricted time-space context that reduces care to fragmented regimes (Francis, 1999). “Economical constraints require cheap labor, task-oriented care, and ritualisation of nursing practice provisions” (Mantzoukas, 2002, p. 16) since organizational culture shapes the context and experiences in which nurses act and react (Gifford, 2002).

One such security apparatus prevalent in nursing culture is pastoral power, exhibited through care provision using specific standardized therapeutic regimes that promote appropriate normalized activities and ways of living. “The power of normalization imposes homogeneity by setting standards and ideals for human beings. Governmentality connects the question of government and politics to the self” (Holmes & Gastaldo, 2002, p. 560). Nurses are the agents that engage in the regulation, promotion, modification, maintenance, and monitoring of client-environmental interaction and set the stage for therapeutic experiences within the organizational context (Hilton, 1997). Often, the culture witnessed in practice is far different from the espoused culture held dear in the heart of ideal nursing culture (Manley, 2000). Nursing engages in a discourse of holistic care yet operates within a constricted time-space context that reduces care to fragmented regimes (Francis, 1999). “Economical constraints require cheap labor, task-oriented care, and ritualisation of nursing practice provisions” (Mantzoukas, 2002, p. 16) since organizational culture shapes the context and experiences in which nurses act and react (Gifford, 2002).  The bureaucratic social structure in which nursing culture operates can be an overwhelming context for the new graduate nurse, as well as nurses with seasoned experience (Philpin, 1999). A palpable tension exists between the industrial organizational culture “with its emphasis on the systematic and procedural work culture necessary for mass production” (Hunt, 2004, p. 189) and the ideal nursing culture espoused and initiated during nursing education. As new graduates enter the work culture, they must learn about and adapt to the collective culture through enculturation and acculturation (Hong, 2001). This socialization process acquaints the new nurse to the norms, beliefs, and values of the nursing culture within the specific health care culture of the hospital or community unit. However, neophyte nurses are not “passive sponges who gradually soak up the collective culture in which they are embedded" (p. 12). They can choose to participate, they can also choose to transform it, at least internally, by rejecting aspects that do not feel right, and embracing those that do. “Individual providers construct and reconstruct their own personal version of the collective culture” (p. 12).

The bureaucratic social structure in which nursing culture operates can be an overwhelming context for the new graduate nurse, as well as nurses with seasoned experience (Philpin, 1999). A palpable tension exists between the industrial organizational culture “with its emphasis on the systematic and procedural work culture necessary for mass production” (Hunt, 2004, p. 189) and the ideal nursing culture espoused and initiated during nursing education. As new graduates enter the work culture, they must learn about and adapt to the collective culture through enculturation and acculturation (Hong, 2001). This socialization process acquaints the new nurse to the norms, beliefs, and values of the nursing culture within the specific health care culture of the hospital or community unit. However, neophyte nurses are not “passive sponges who gradually soak up the collective culture in which they are embedded" (p. 12). They can choose to participate, they can also choose to transform it, at least internally, by rejecting aspects that do not feel right, and embracing those that do. “Individual providers construct and reconstruct their own personal version of the collective culture” (p. 12).  An unfortunate backlash of the tension and pressure of the organizational culture that surrounds nurses is a high incidence of horizontal violence, or staff conflict, especially poor colleague relationships (Farrell, 2001). When this is experienced by new nurses, it can be particularly paralyzing, as “junior nurses are quickly socialized into a culture of nurse-to-nurse abuse. This helps to demonstrate the hierarchical structures and preserve the status quo” (p. 28).

An unfortunate backlash of the tension and pressure of the organizational culture that surrounds nurses is a high incidence of horizontal violence, or staff conflict, especially poor colleague relationships (Farrell, 2001). When this is experienced by new nurses, it can be particularly paralyzing, as “junior nurses are quickly socialized into a culture of nurse-to-nurse abuse. This helps to demonstrate the hierarchical structures and preserve the status quo” (p. 28).  If nurses feel alienated, with no control over their own practice, they may experience resentment and frustration which is expressed to those near at hand, usually other nurses and perhaps even their own clients. Nurses are expected to be constantly vigilant, in a “state of watchful attention, of maximal physiological and psychological readiness to act and having the ability to detect and react to danger” (Meyer & Lavin, 2005, p.1). This vigilence coupled with heavy workloads, extreme time pressures, and limited space in which to work creates a very real cultural context of contention. If one nurse sees another nurse as doing less, making mistakes, or invading their space, violent or abusive behaviors can easily occur, perpetuating the cycle of tension and distress. Wesorick (2002) addressed this issue by encouraging health care management and nurses to create healthy, healing work cultures in nursing, “to transform practice cultures so the essence, uniqueness, and outcomes of professional practice will be realized” (p. 18). She points to cultural transformation as the key, which “requires continuous commitment to create a space worthy of the presence, efforts, and needs of those who provide and receive care” (p. 24). This is important not only for a strong healthy nursing culture in context, but for the optimal provision of client-centered, holistic care.

If nurses feel alienated, with no control over their own practice, they may experience resentment and frustration which is expressed to those near at hand, usually other nurses and perhaps even their own clients. Nurses are expected to be constantly vigilant, in a “state of watchful attention, of maximal physiological and psychological readiness to act and having the ability to detect and react to danger” (Meyer & Lavin, 2005, p.1). This vigilence coupled with heavy workloads, extreme time pressures, and limited space in which to work creates a very real cultural context of contention. If one nurse sees another nurse as doing less, making mistakes, or invading their space, violent or abusive behaviors can easily occur, perpetuating the cycle of tension and distress. Wesorick (2002) addressed this issue by encouraging health care management and nurses to create healthy, healing work cultures in nursing, “to transform practice cultures so the essence, uniqueness, and outcomes of professional practice will be realized” (p. 18). She points to cultural transformation as the key, which “requires continuous commitment to create a space worthy of the presence, efforts, and needs of those who provide and receive care” (p. 24). This is important not only for a strong healthy nursing culture in context, but for the optimal provision of client-centered, holistic care.